Cuba, Intimately Documented: The Work of Lisandra Alvarez Valdés

Lisandra Alvarez Valdés is a Cuban photographer and professor of Photography and Typography at the Higher Institute of Design, the university where she also studied.

Surrounded by photographer friends, Lisandra began to take an interest in photography between 2018 and 2019, observing how deeply those around her engaged with their cameras. At the time, however, her own attempts at photographing were still rare, partly because she was deeply focused on her university studies, and partly because she was living in a place that didn’t inspire her to press the shutter.

In this initial phase, Lisandra says she began with street documentary photography, mainly because that was what the photographers around her were doing. The self-reflection on following other paths, ones more connected to her own style and intuition, would come later.

Her growing involvement with photography sparked a desire to learn more about the work of other photographers. At the time, internet access in Cuba was very limited, so she would go to a park, the only one with a Wi-Fi signal, to try to download materials about photographers, despite the poor connection. Lisandra’s training was therefore largely self-taught, through both seeking external references and learning from friends who were already photographing, often asking them questions about how the cameras worked, for example.

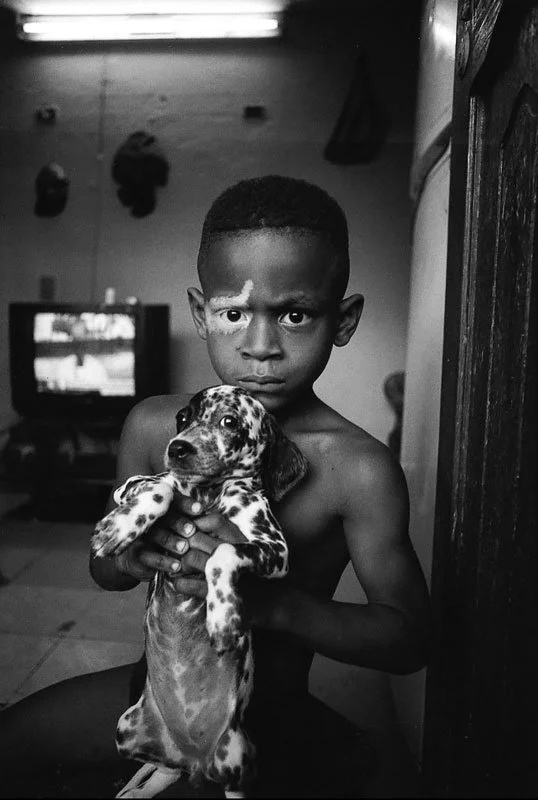

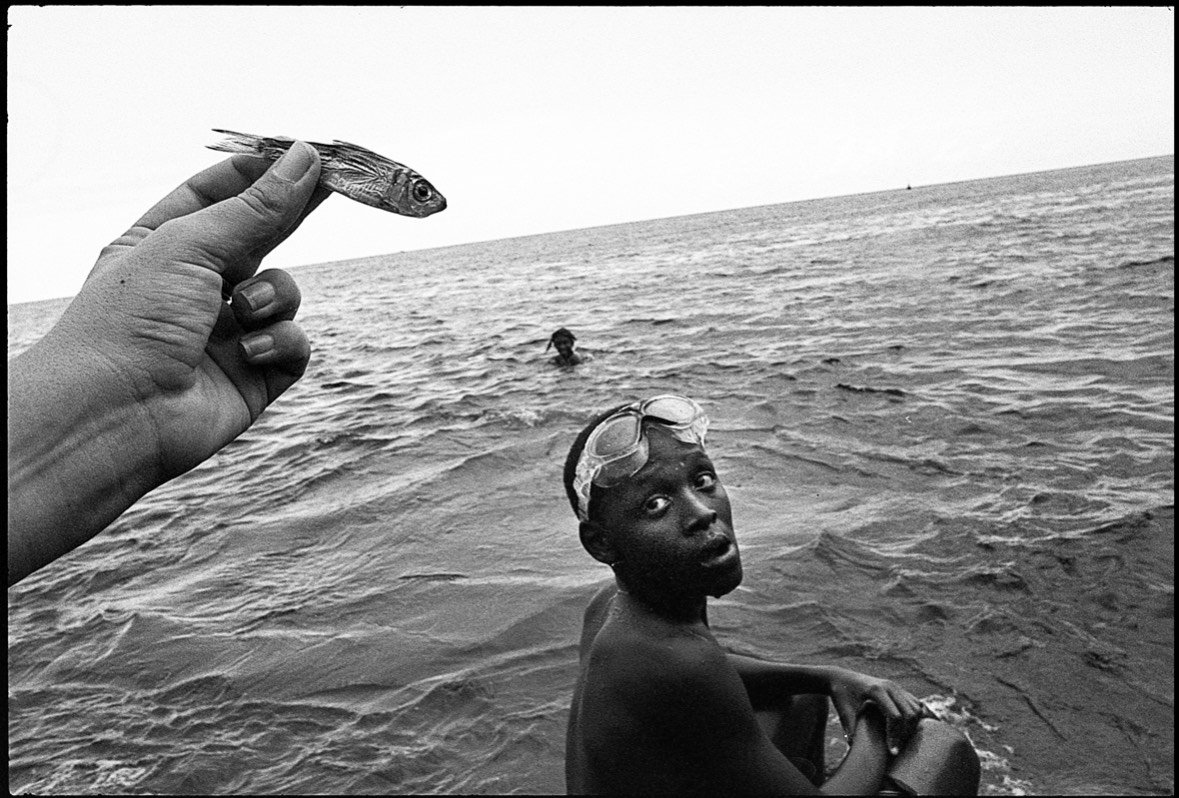

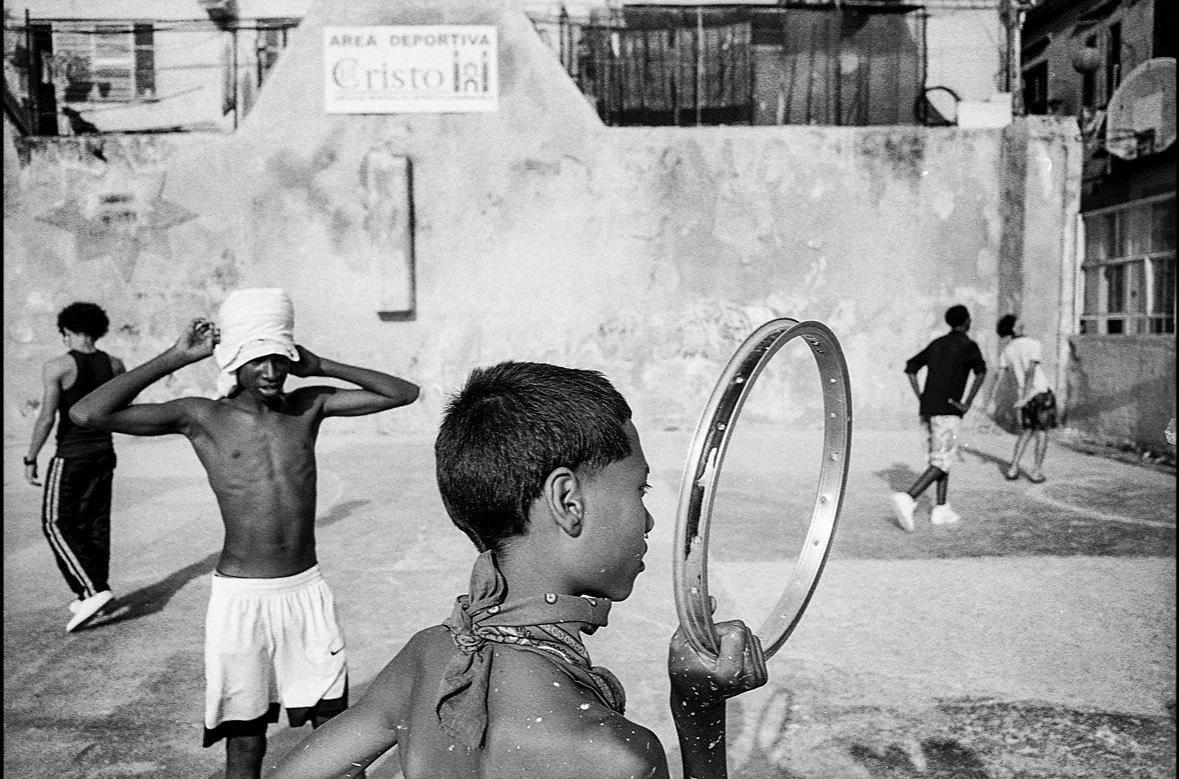

While that part of the city inspired Lisandra to develop her photographic style, it is also worth noting that the Cuba emerging from her photographs is a particular one — surreal and magical, but not stereotyped, as is often the case in foreign portrayals that tend to depict the island without truly attempting to understand it.

Lisandra knows Cuba, but she knows that the country is made by its people, that Cuba is, above all, those people, with their stories, their names, their paradoxes, with their children who are expected to have better living conditions in the future of a country that has already gone through so much.

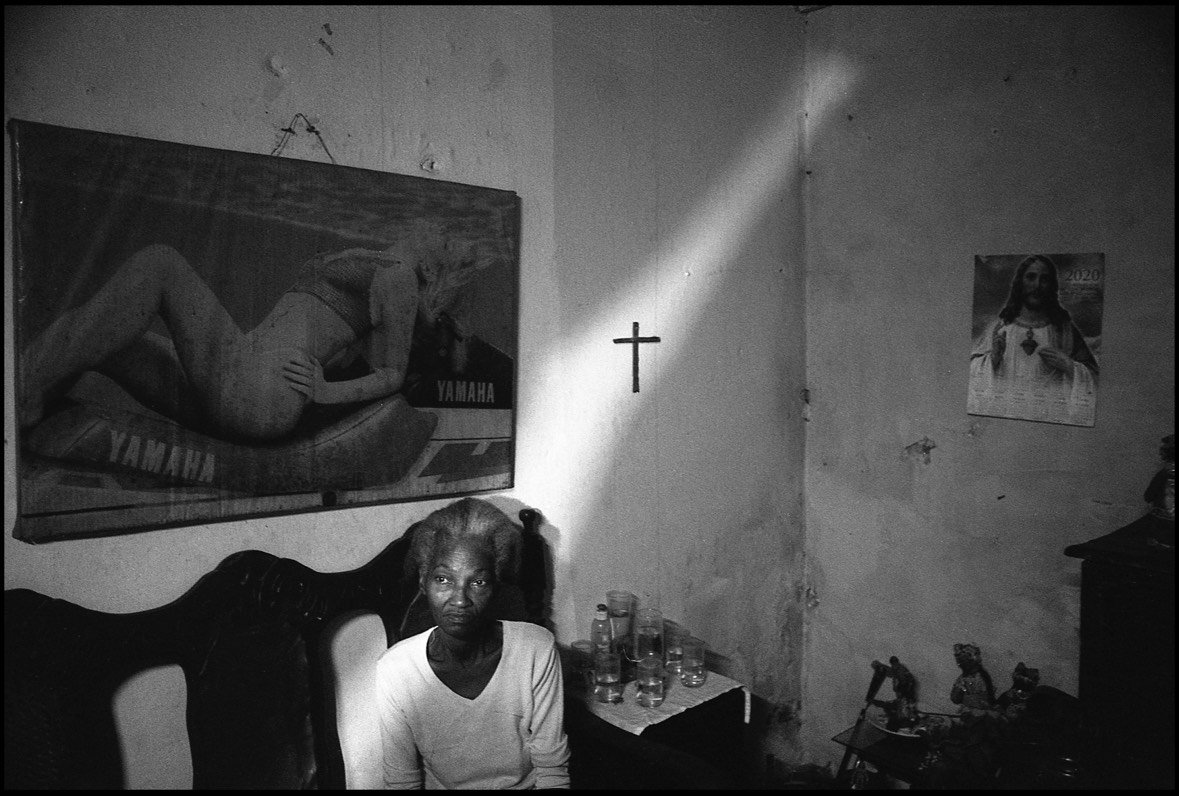

But Lisandra not only knows, she respects. She looks and photographs, but she also interacts and listens, and perhaps that's why her images are so rich with stories. To the photographer’s own narrative are added the stories told by the landscapes, the buildings and the stones, the flora and fauna, alongside the stories of each person, like the elderly woman with a vacant gaze in a room filled with religious symbols and a motorcycle brand advertisement.

How would you describe your photographic style?

I’ve always thrown myself into street photography, and when I started working in the neighborhoods of Centro Habana and Habana Vieja, I discovered a world I already knew existed, but not in such depth. These places are completely surreal, and I believe I connected deeply with that atmosphere and with the people who live there. That connection is fundamental to my work.

I don’t consider myself a classic street photographer; rather, I use the street as a tool to find the stories I want to tell. I would describe my work as having an “intimate documentary” approach, since I almost always need to connect with my subjects before photographing them, maybe a brief conversation, a minimal exchange, even if just visual. But I’m almost never the kind of photographer who captures moments instantly while walking. I need to get involved with the scenes.

At what moment do you feel that an image “worked,” that you managed to capture what you wanted?

I don’t think there’s a formula to explain when an image is good or not, it simply has to make an impact, it has to shout. I also don’t believe it needs to be complex to be a good image. I feel satisfied when a photo says more than what’s visible at first glance. I like images that transmit something, that pull you in, that make you feel as if you’re inside the scene, almost sensing on your own skin what’s happening.

Do you have any ongoing projects or a photographic dream you’d like to realize?

Up to now I have two projects, let’s say with a concept or idea. I’m working with a children’s circus in a neighborhood in Centro Habana and in a house where women and small children live, and I’ve been documenting everything that happens there since 2022. My dream would be, first of all, to have a body of work that I feel satisfied with. I think that’s the first barrier: to feel fulfilled with the work done. And well, to be able to take the work to different places, not only in Cuba.

How do you see photography in Cuba today? What do you think are the biggest challenges and the greatest strengths?

In Cuba, photography is becoming more and more of a challenge. The general crisis continues to affect everyone who chooses this path, especially those of us who work with analog photography, which is not only very expensive but also even more difficult, since we have to import every kind of supply through a friend or acquaintance traveling to the island.

It’s also increasingly difficult to dedicate time to it, since you constantly have to work just to make ends meet. I think you need a great deal of passion to keep going. We’ve also seen an exodus of many young people who were developing a promising body of work but decided to leave the country in search of a better future. I think that sums it up: you need to be deeply committed to that passion in order to persist and see whether there’s any chance of success, which isn’t easy either.

Cuba is a photographic destination that attracts photographers from all over the world. Why do you think that happens? And do you perceive any difference between photos taken by Cuban photographers and those by foreign photographers in Cuba?

I think Cuba is a photographic destination, first because it’s a very surreal country, and second because Cubans are generally very open to having their photo taken, which, I’ve been told, is not so easy in other countries, especially with children. People here are very warm, and that’s also very attractive and makes it a place many photographers are drawn to.

Images by foreign photographers are often taken from a more distant or superficial perspective. Of course, there are always people who have come and developed exceptional work, like Juan Manuel Díaz Burgos or Ernesto Bazán, but I definitely believe you have to return repeatedly, or stay for a long period, to go deeper and capture reality more intimately.

How do you decide when to photograph in black and white or in color?

I usually prefer black and white because I believe color has a different connotation and, above all, it should communicate something beyond composition. So far, I only have one project in color on 120mm because the space simply asks for it to be that way. I think in this case it’s quite evident, since the atmosphere is sometimes very intense, and the fact that it’s in color adds all the beauty and warmth that I want to convey.

.

.

.

Do you work with analog photography? Is there a special reason behind that choice?

The choice to work with analog photography is simply because I feel it aligns better with my process. I’m not the kind of photographer who shoots everything I see, I’ve even come home many times without taking a single shot, and that’s something I’ve learned from working with film: to be much more selective.

Also, the result captivated me from the beginning, as did the process of developing at home, it’s all very artisanal, and I haven’t been able to detach from that feeling. Color, especially, has a completely different look compared to digital color.

Are there people who have influenced your photographic style or vision?

I’ve been very inspired by the work of Gordon Parks, Mary Ellen Mark, Vivian Maier, Raúl Cañibano, Manuel Almenares, and I recently discovered the work of Brazilian photographer Tiago Santana, which I love.

Do you think the world of photography is more difficult for women?

Yes, I do think it’s more difficult for women, although not from the point of view of visibility, because I believe that right now we’re actually winning a battle in that regard. There are many women’s communities actively working to bring that visibility to the world.

I think the greater difficulty lies in the fact that we usually have to carry many more responsibilities from daily life alongside our photographic work. Also, in my experience in Cuba as a woman photographing in the streets, there’s a lot more unwanted attention, sometimes even harassment, which male photographers don’t usually experience.

At the end of the text, I mentioned the photograph you took of a woman with a distant gaze. That’s one of my favorite images of yours. Could you tell me a bit about it?

This image was taken in Centro Habana. We were photographing a “santo” party, as we call it here in Cuba, which is like a Santería ritual. And she was there, she was a neighbor. It’s a place in very bad condition, a solar, as we also call these old buildings where many families live in small rooms. To be honest, the santo party didn’t catch my attention much, but as soon as I looked to the side and saw the small space where she lived and all the decoration with religious symbols, I knew I had to take a photo. This image won an award at Women Street Photographers in New York, and it has really brought me some very good moments.

Finally, could you tell us a bit about your project with the circus?

The circus project is something I’ve been developing gradually over time. Cirhabana Circus, that’s the name, is a neighborhood children’s circus in Centro Habana, and it runs every day after school from 5 to 8 p.m.

I first went there during a workshop we were teaching, and the place immediately captivated me, partly because of the old industrial structure, but above all because of the children’s ability to play and transform their bodies. These are kids with no professional training, just children whose parents maybe want to keep them entertained after school.

There, I’ve been trying to explore a more abstract way of working. It’s a very challenging space, first because there’s so much happening all around, and second because it’s very dark, which, in my case, working with analog photography, makes things even more complicated.

.

Interviewed and written by Ana Cichowicz

.

Photos © Lisandra Alvarez Valdés

.